One of the most-touted aspects of social media when it comes to realtime global warning is its claimed ability to "beat the news" and deliver the earliest glimmers of tomorrow's biggest stories before anyone knows what's happening. The reality is that for the majority of stories news media actually delivers the first measurable signal, while one of the very first global alerts of Covid-19 was measured from GDELT's news data, long before it ever became a story on social media platforms. Far less appreciated and studied, however, is the degree to which the speed of social media comes with the dangers of viral falsehoods causing false alerts.

Last week, President Recep Erdoğan of Türkiye, like many political campaigners before him across the world, became ill during a news interview, speaking by video conference two days later and returning to the campaign trail in person a few days later. Yet, by the following evening news was sweeping social media and fringe corners of the media that Erdogan had suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized, with many reports alluding to or claiming outright that he had just hours to live and preparations were being made for the transfer of power. Journalists from around the world urgently sought clarification on the president's health. In urgent text messages, phone calls and emails, editors from some of the world's most recognized news outlets spread the rumors of Erdogan's imminent demise, notifying colleagues what they were seeing on social media and asking what they could verify. Rumors ranged from the president being in a coma to his having just hours to live.

For those trading on speed, social media delivered: a realtime stream of rumors spreading like wildfire. In contrast, despite news editors privately spreading the health rumors through their networks as they urgently worked to either confirm or refute them, most major news outlets around the world did not report on the heart attack rumors because they deemed them not yet credible in the absence of any corroborating evidence or statements and, most importantly, the lack of externally visible government preparations (such as the urgent summoning of key government personnel) that would most likely accompany a legitimate health crisis of the magnitude being reported on social media. In short, on social media the rumors spread unfettered as truth, while the mainstream media refrained from reporting on what it could not verify and which seemed at odds with all other available evidence.

During the critical 24 hours surrounding the rumor, this was initially cited by many as evidence of the superiority of social media over its legacy brethren: those relying on Twitter were the first to know what the legacy media, even hours later, failed to report. When Erdogan appeared by video link the following day and then returned to the campaign trail in person shortly thereafter, those voices once again fell silent. This has been a common theme we have observed across the globe: the speed of social media is at odds with the necessity of taking the time to verify information before reporting it and when a breaking story is spreading virally across social media without mainstream media uptake, this is a key signal that all may not be as it appears.

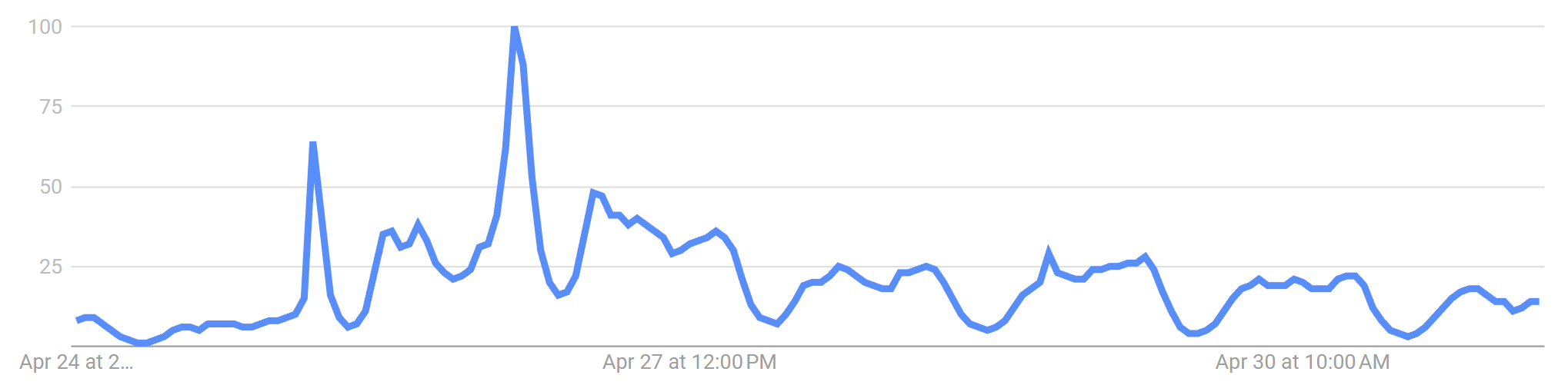

The timeline below shows Google search interest in "Erdogan" and "heart attack" showing searches began to take off around 11AM EST, accelerated by 3PM and peaked from 4-5PM EST, collapsing until 9PM, then rising again through 1AM EST the following day, then fading again.

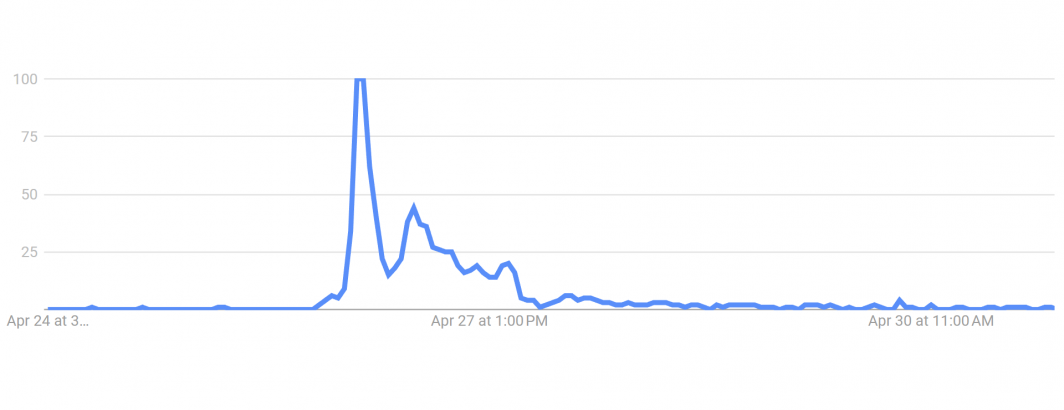

Of course, searching for the English phrase "heart attack" limits the query above to English searches, likely reflecting US interest. Thus, the query below uses the multilingual Google Trends topic reflecting all search activity for President Erdogan across all languages Google supports. It shows the same overall pattern, with a peak at 4PM EST.

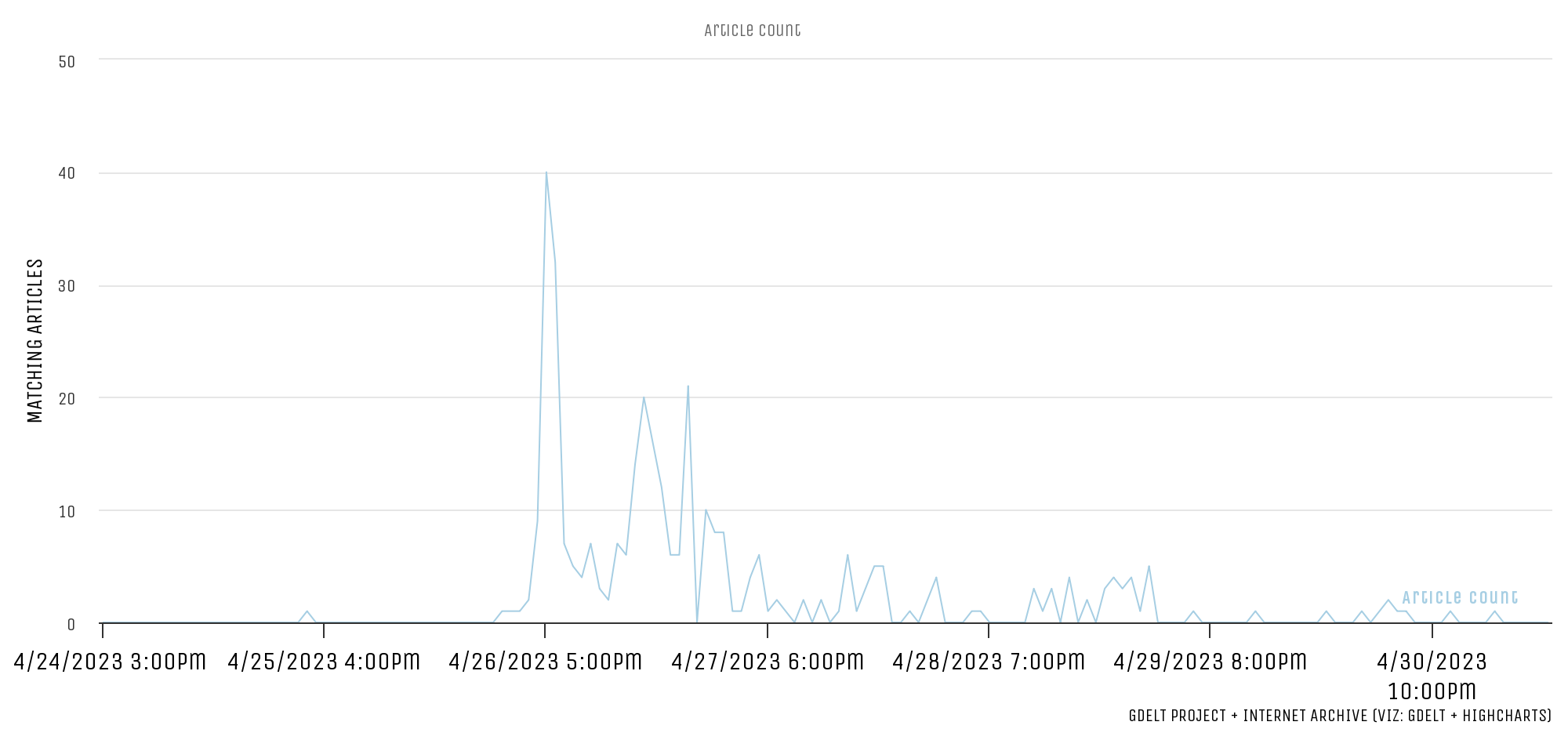

If we look at global news coverage of "Erdogan" and "heart attack" we see a roughly one hour lag from the Google Trends data, peaking at 5PM EST. The reason for this lag is visible in the nature of this early coverage: it largely refuted the rumors spreading on social media, with the delay stemming from the time it took to get official government statements and to compile evidence that further suggested the rumors were unlikely to be true.

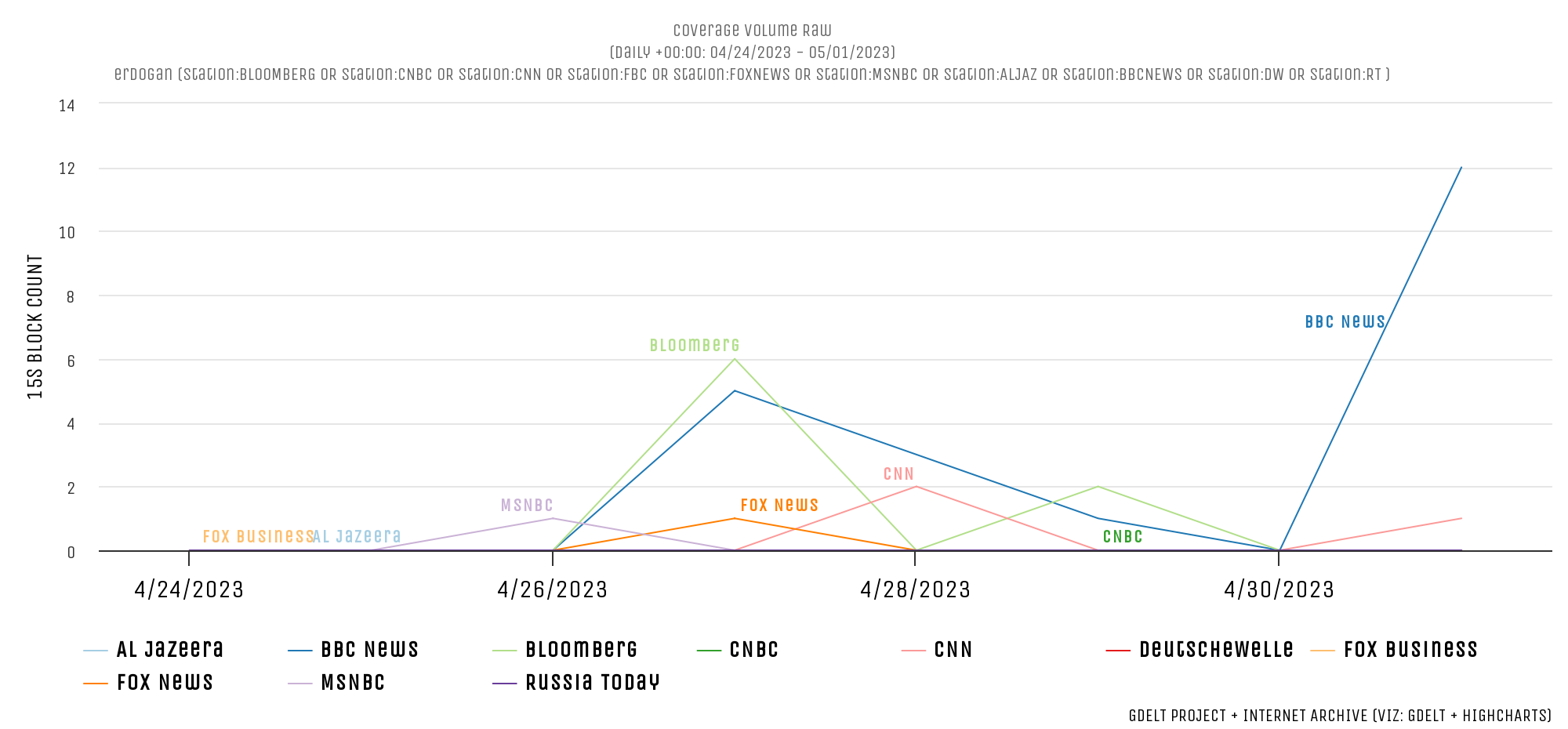

Realtime television news coverage, which would be expected to break live into its coverage to report the imminent death of a major world leader, also did not run the story, providing yet more evidence as the hours went by that the social rumors were less and less likely to be true.

Putting this all together, social media's speed is often cited as making it possible for social-based early warning systems to "beat the news." Not only does mainstream media often provide the earliest measurable warning of major stories, but social media's prioritization of speed over verification means the signals derived from it on major stories can lead their users woefully astray.