We are incredibly excited to announce the debut of the Africa and Middle East Global Knowledge Graph (AME-GKG) special collection, providing access to the codified GKG dataset created as part of the recent study “Cultural Computing at Literature Scale: Encoding the Cultural Knowledge of Tens of Billions of Words of Academic Literature.”

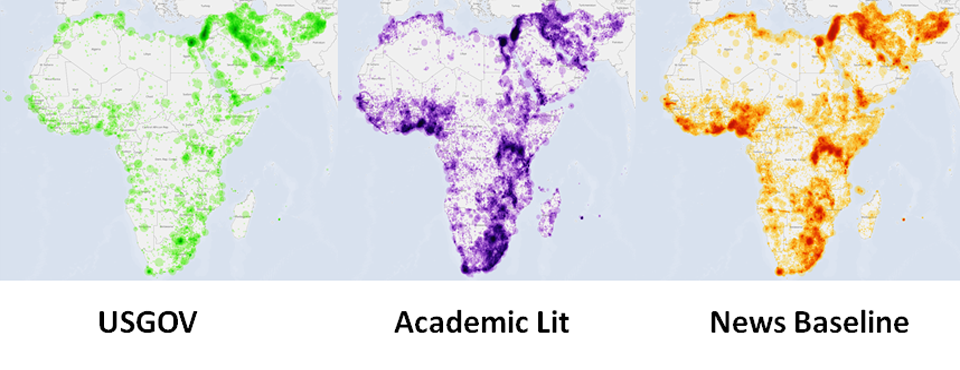

Representing the first large-scale content analysis of JSTOR, DTIC, or the Internet Archive ever performed, this latest GDELT collaboration, with Timothy Perkins and Chris Rewerts of the US Army Corps of Engineers, codified the entire holdings of JSTOR (academic literature), declassed/unclassed DTIC (US Government publications), and the Internet Archive (the open web) relating to humanities and social sciences academic literature about Africa and the Middle East and built a massive knowledgebase that encodes all of the underlying socio-cultural knowledge from more than 21 billion words of material. It includes the majority of ethnic, religious, and social groups, 275 themes, geography, and the entire citation graph, which making it possible to literally map what’s been studied in the academic literature about a particular area dating back half a century, and, through a new “find an expert” service, get back a list of the top scholars whose works covering that group/location/topic/combination therein are the most heavily-cited.

In the hopes of seeding new frontiers of research and in particular the ability of quantitatively codified academic literature to offer a transformative new lens through which to reimagine the way we access and understand our collective knowledge of culture, today we are officially unveiling access to the underlying GDELT Global Knowledge Graph (GKG) Version 2.0 files created as part of the study. (See the GKG 2.0 Codebook for more details on the file format.) Like all GKG files, the datasets below do NOT contain the text of the original documents – they contain only the codified metadata computed from those documents. Each entry includes either a URL to access web-based documents in the case of the Internet Archive, CiteSeerX , or CIA collections, or a CORE, DTIC, or JSTOR DOI to access materials from those collections. In the case of JSTOR, you can use this DOI to access the original document using your JSTOR subscription if your institution is a subscriber, while for CORE and DTIC you can use this DOI to access the original document using the search features on their respective websites. Again, these files do NOT contain the text of the source documents, only the codified metadata computed from each of them. Each entry contains all of the original GKG 1.0 fields along with several new fields debuting in the GKG 2.0 format, including a codified representation of the key attributes of the references cited in each document. The full collection is 7.4GB compressed and 39.6GB uncompressed.

Note that to assist in certain classes of analysis, the metadata entries in this collection have been standardized through automated normalization and coreferencing. In the case of this collection that means that if an article introduces “United States President Barack Obama” and subsequently refers to “Obama,” all of those subsequent references will be normalized as references to his full name of “Barack Obama” and coreferenced to imply a mention of the “United States” and the functional role of "President." Normalization and coreferencing at this scale on this diversity of formats and language use over this many decades is highly experimental and may lead to unexpected behavior or interpretive considerations in some documents. It was applied to this collection to assist in certain types of analyses that require such normalization. Note further that all citations were extracted completely automatically using the ParsCit software and there are considerable errors in the extracted citation metadata due to the difficulty of correctly interpreting citations across so many citation formats and standards. Citations are not normalized or otherwise corrected, and should be treated using the same kinds of post-processing applied to other automatically-extracted citation data. The complexities of processing such an incredible diversity of materials spanning so many styles and formats and spanning multiple decades of linguistic patterns, not to mention the inclusion of OCR error and PDF parsing, and the difficulties of tasks like disambiguation and coreferencing applied to documents that can span hundreds of pages and use highly formalized and highly stylized language, mean that this collection has a considerably higher error rate than the GKG encoding of contemporary daily news material and applications should exercise appropriate postprocessing and normalization procedures that take these errors into consideration. While far from perfect, it is our hope that by releasing these GKG 2.0 files underpinning the study, the data will be able to seed new frontiers of research and inspire a whole new way of thinking of computing on culture.

- GDELT Global Knowledge Graph (GKG) Version 2.0 Codebook.

- Read the Full Paper Describing the Collection.

- AME-GKG.CIA.gkgv2.csv.zip (26MB)

- AME-GKG.CORE.gkgv2.csv.zip (1.7GB)

- AME-GKG.DTIC.gkgv2.csv.zip (1.7GB)

- AME-GKG.IADISSERT.gkgv2.csv.zip (802MB)

- AME-GKG.IANONDISSERT.gkgv2.csv.zip (129MB)

- AME-GKG.JSTOR.gkgv2.csv.zip (2.9GB)