With the proliferation of cheap high-resolution digital imaging hardware and falling storage costs, mass digitization initiatives have gone mainstream, bringing billions of pages of historical material into the electronic era. Today three of the largest single repositories of digitized books are the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, and Google Books collections. One of the greatest challenges remains how to make these vast archives more amenable to data mining and bulk analysis and to gain a better understanding of how the collections differ and if analyses using one collection can be replicated using another. Here the results of a brief comparison of the three collections are presented, showing they align closely prior to 1922, but offer substantially different results in the copyright era.

The Datasets

The Internet Archive Texts collection encompasses over 8,000,000 total volumes, of which 2.2 million are found in the American Libraries collection examined here. It is the most open of the three collections, making the fulltext of all volumes freely available to anyone through direct download from its website. The Archive’s Advanced Search interface allows search results to be downloaded in JSON, XML, HTML, CSV, or even RSS format, including both the item identifier and most metadata fields –a search for “collection:(americana)” was used to retrieve a list of all 2.2 million American Libraries works in CSV format for this analysis. All Archive web pages accept “&output=json” added to the URL to view the results in machine-friendly format. A small cluster of Google Cloud machines were used to fetch the metadata and ASCII text URL for all of the books in parallel, and a second pass was used to download the fulltext files themselves. Though the Archive’s Advanced Search service does not permit fulltext search, custom collections based on title, author, subject tags, or other metadata can be used to rapidly compile customized extracts that can be downloaded in minutes. The availability of modern machine-friendly formats like JSON and the ability to download content in parallel via the open web, combined with the fully open-access model, makes working with the collection trivial. Other Archive content not in the public domain is available for analysis using virtual machines running at the Archive as part of its Virtual Reading Room program.

The public domain HathiTrust collection is available for bulk download for academic research, but requires a signed institutional legal agreement and preapproval of the research to be conducted, the output files made available from that research, and the computing platform used for the research. Only authorized project personnel are permitted to access the fulltext, and any subsequent research projects must be similarly preapproved before accessing the content. HathiTrust reserves the right to restrict the kinds of research and output files that can be produced from its collections – in the case of the broader project from which the results here are derived, it required that the list of quoted statements extracted from each book be withheld from public release for a subset of the collection. Content is delivered by rsync download or USB drive at a peak of 50MB/s. Each book is delivered as a ZIP file containing one ASCII file per page, requiring unzipping and repacking into single text files. Book identifiers contain an array of characters such as dollar signs, forward slashes, and plus signs that are not recommended in many file systems, and files are delivered in a deeply nested tree hierarchy, requiring remapping into a linear filesystem. Metadata is provided in XML MARC format, requiring extensive knowledge of MARC format to extract the desired fields. Additional HathiTrust non-public-domain HathiTrust content is available via the HathiTrust Research Center’s Data Capsules program.

Finally, the Google Books Ngrams collection is perhaps one of the best-known datasets for examining word usage over time through books. Created as a companion to a 2011 Science article, just over 4.5 million volumes (708,000 of them published from 1800-1922) were processed by Google to compile a list of word and phrase frequencies up to five words long. Part of speech tagging and other linguistic analysis have been added to the system in subsequent years to create an interactive user-friendly viewer for tracing the popularity of a word or phrase over time. Data runs from 1505 through 2008 and, unlike the other two collections, shows no decrease in the number of books after 1922, exhibiting exponential growth starting in 1943. The word frequency tables can be downloaded for bulk data mining, however Google does not allow the underlying text to be accessed through any means, making it impossible to apply data mining tools that require analyzing words in context.

A Brief Comparison of the Three Collections

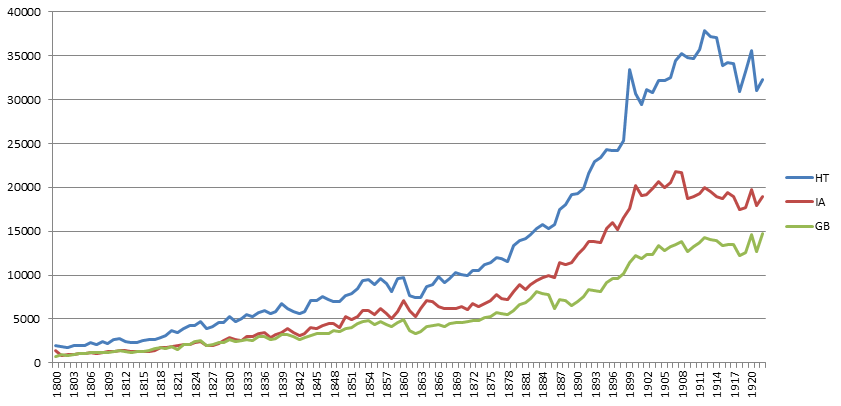

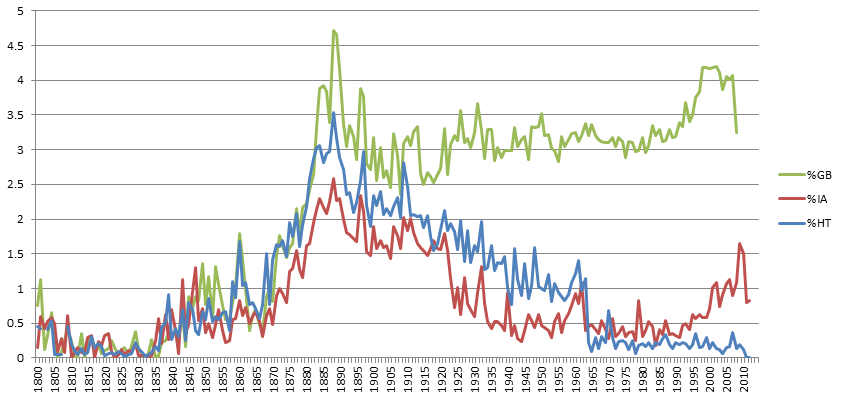

The three collections have nearly identical growth rates in the number of books per year from 1800 to 1922, with HathiTrust having the most books, followed by the Internet Archive and then Google Books. All three increase through the American Civil War, level off for about a decade, then increase exponentially through around 1900, before leveling off, while HathiTrust and the Internet Archive then decline through 1922.

The HathiTrust and Internet Archive collections abruptly end in 1922, dropping to just 10-20% of their former volume. Google Books, however, exhibits no measurable change in volume across the copyright barrier, continuing linearly through 1943, when it begins increasing exponentially through the data’s endpoint of 2008. Google has never published a master list of the books it includes in its collection, so it is impossible to know whether the collection’s composition changes in any meaningful way after 1922, but searches for a variety of person names and common phrases show no visually discernable changes across the copyright barrier.

While the absence of a catalog listing for Google Books makes it impossible to know what inclusion criteria were used, both HathiTrust and Internet Archive have substantial overlaps in their holdings. Roughly 37% (and as high as 53% in 1822) of Internet Archive books prior to 1923 have identifiers ending in “goog” indicating they come from the Google Books collection. This drops to less than 1% per year after 1922. Similarly, 8% of HathiTrust books prior to 1923 include an Internet Archive Identifier (dropping to less than 1% afterward 1922), indicating they came from the Archive. Just over 93% of HathiTrust books in total have a MARC code indicating Google as the provider of the digitization, suggesting that HathiTrust draws heavily from the Google Books corpus. Of course, these numbers reflect only those books officially marked as coming from Google or the Internet Archive, and the real overlap could be far higher.

The HathiTrust and Internet Archive collections also have a certain degree of internal duplication in which the same book is scanned multiple times (either by accident or due to a better copy being available later from a different library). For example, “Charles Darwin: Memorial Notices Reprinted from ‘Nature’” exists in at least three copies in HathiTrust, from Harvard, University of Wisconsin, and the University of Illinois, while “Darwin, Goethe und Lamarck” has two copies, both from the University of Michigan. Similarly, in the Internet Archive, copies of the “Foundations of Botany” can be found from the New York Botanical Garden and University of California. Overall, 34% of HathiTrust books share the same author and title with another book published the same year, while 25% of Internet Archive books do. Duplication in the Internet Archive appears to be roughly constant from 1800 to 2015, while HathiTrust’s duplication rate has decreased from 50% in 1800 to around 10% today, with changes of up to 10-20% by decade.

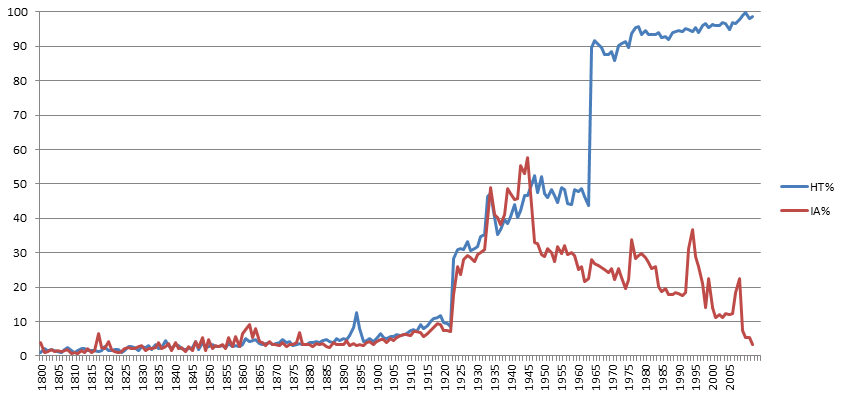

The HathiTrust and the Internet Archive collections appear to have adopted markedly different acquisition strategies in the post-1922 era, as seen in the figure below, which plots the percent of books in each of the two collections that are US Government publications. With the transition to the in-copyright era in 1923, both rely heavily on US Government publications, increasing their share from around 7% in 1922 to nearly 30% by 1924, then increasing rapidly to around 50% by 1944. Beginning in 1946 the Internet Archive has steadily decreased the percentage of its books from the Government, to just over 3% today. HathiTrust books, on the other hand, continue at around 50% Government publications through 1963, then jump to 90% in 1964 and increase steadily to 99% today. This suggests that analyses using either collection will be heavily biased towards US Government topics and language use post-1922 and studies of the two collections will likely deviate substantially after 1945 given their markedly different compositions over the last half century.

Turning to the subject tags provided in each collection, the top four tags for books published 1800-1810 are Bible, English Hymns, Church of England, and American Sermons for the Internet Archive, and United States, English Poetry, England, and English Literature for HathiTrust. From 1850-1860, the top four tags for Internet Archive books were Bible, Slavery, English Hymns, and Medicine, while for HathiTrust they were United States, Science, Great Britain – History, and Slavery. From 1910-1920 the top four Internet Archive subject tags were World War 1914-1918, Theses, Abraham Lincoln, and Education, while for HathiTrust they were United States, World War 1914-1918, United States – History, and Science. From 1990-2000 the top Internet Archive tags were Medicare, Delegated Legislation, Administrative Law, and College Student Newspapers and Periodicals, while for HathiTrust they were Administrative Law – United States, United States, United States – Armed Forces, and Budget – United States. The Internet Archive therefore seems to have a greater emphasis on religious texts, while HathiTrust has a greater emphasis on England, though this is likely due to the use of the American Libraries collection for the Internet Archive books. The 1990-2000 topics suggest that in the modern era the Internet Archive has emphasized university materials like student newspapers, while HathiTrust has focused on legal and budgetary texts.

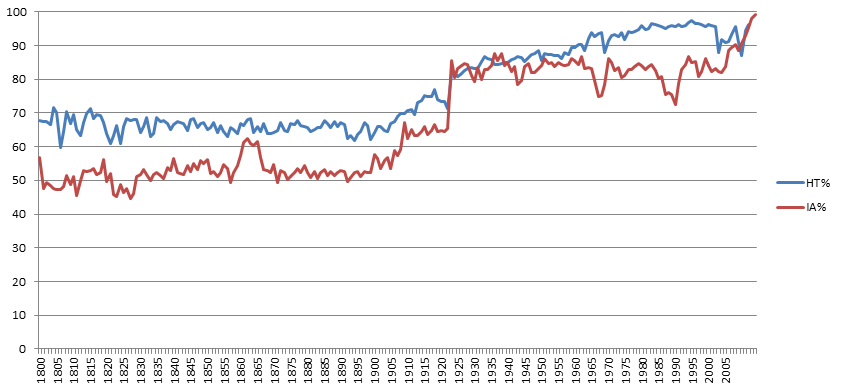

It should be noted that the availability of subject tags changes considerably over time in both collections, as seen in the timeline below. Only about half of Internet Archive books have subject tags through 1900, then increases steadily to 65% through 1922, before jumping to 85% in 1923 where it remained through the late 2000’s and is now nearly 100%. HathiTrust similarly saw subject tags hover steadily around 65-70% through 1900, before increasing steadily to around 95% by the early 1980’s. Subject tags are therefore available for just half of books published before 1923, making it more difficult to use them as a means for accessing earlier content.

Of course, the most important question revolves around how these differing characteristics affect the results derived from analyzing the three collections. In other words, will an analysis based on one collection be replicable using the other two, or does the dataset used have an impact on the results? If an analysis using Google Books yielded different results than one using the HathiTrust or Internet Archive collections, this would have significant ramifications for the future of research using these digitized book archives.

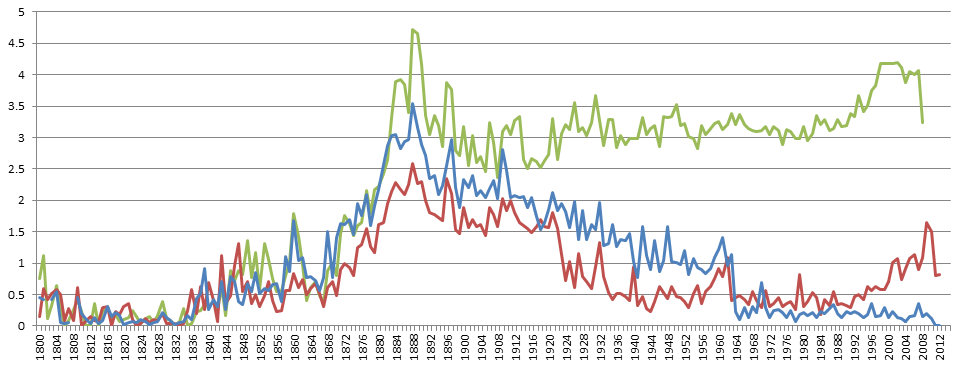

The timeline below shows the percent of books in each collection by year that mention “Abraham Lincoln” at least once in the text. (Since the Google Books NGram viewer shows results as a percentage of words instead of books, the results here were calculated directly from the ngram files themselves, which report the number of matching volumes). The three collections track closely through 1939 (though the Archive has a substantially sharper peak in 1865). After 1939, the HathiTrust and Internet Archive collections are nearly identical, while Google Books shows a roughly similar inverse bell curve, but with a much higher percentage of matching books. In this case, an analysis using either of the three will yield highly similar results through 1939, but deviate after that.

Similarly, the timeline below repeats the same process for “Charles Darwin.” This time all three collections line up nearly identically through 1922, though HathiTrust shows a slight decrease in matches from 1912 to 1922 when the other two are roughly level. Beginning in 1923, however, the three collections diverge sharply. Google Books shows a steady volume of matches, with no measurable change before/after 1922, while both HathiTrust and the Internet Archive show a steady decline in mentions through 1964, when HathiTrust levels off and the Internet Archive begins to show an increase in mentions through present.

This reflects a crucial finding – analyses performed with any of the three collections will yield nearly identical results through the end of the public domain era in 1922, but may diverge substantially after that, based on the very different collection strategies used by the datasets in the copyright era. Given that only the HathiTrust and Internet Archive collections offer access to the underlying fulltext, analyses requiring fulltext access should restrict themselves to the pre-1922 era.

Mapping the World of Books

Finally, putting all of the pieces together, the map below shows a brief example of the kinds of macro-level new insights that become possible when data mining vast archives of digitized books using these collections. In 2007 Google published a set of four maps showing the locations of major cities mentioned in books published in the 1800’s to visualize “the Earth viewed from books.”

The interactive map available below explores this same question, but applies fulltext geocoding to the entire Internet Archive Americana collection 1800 to 2013 (the last year of sufficient volume) to display a dot on the map at every location mentioned in at least 15 books published that year. The algorithms used were designed for contemporary location names, so there will be a certain level of error in the map, especially for regions that have undergone substantial changes in the names of their cities, but nonetheless, the map presents a fascinating view of the evolution of the focus of English-language literature held by American libraries over the past two centuries. Click on the image below to launch the interactive map and zoom into the United States to see the Westward expansion of American literature, or zoom into Europe to see the heavy emphasis on central Europe with little coverage of Eastern Europe through the 1800’s. Most strikingly, notice how substantially the map changes in 1923 with the transition to the in-copyright era, showing how substantially the geographic focus of the Archive’s Americana collection changes in this period. Then take a look at the same map, but created based on the HathiTrust collection 1800-2011 (using a threshold of 40 books and 80 total mentions in a year).

Putting It All Together

What does this all mean? For analyses that only need to measure the relative popularity of a word or phrase over time, the Google Books NGram collection will likely be the best choice given its intuitive user interface and the fact that it appears to be unaffected by the transition to the copyright era. Research needing access to fulltext should restrict itself to the pre-1923 era and will likely find the Internet Archive corpus the easiest to work with, since it is available via an open access model without the institutional legal contracts and research prereview and preapproval process of HathiTrust. However, HathiTrust also offers access to a much larger post-1922 corpus of in-copyright texts via their Data Capsules model. While examining that collection was beyond the scope of this analysis, it may offer unique access for those needing fulltext access to a more representative corpus of post-1922 materials.

As the animation above shows, there is enormous potential in making these collections available for academic research at scale. With the support of Google the Internet Archive and HathiTrust book collections have been fully processed through the GDELT Project metadata pipeline, extracting person and organization names, more than 4,500 emotions and themes, and fulltext geocoding each book, and all of this metadata has just been released through Google’s BigQuery service, along with the fulltext of all Internet Archive books published between 1800 and 1922.

I would like to thank Google, Clemson University, the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, and OCLC for their assistance and support in this analysis.