Given my PhD in library and information science, I am personally fascinated by the history of how societies across the world have archived and preserved information to be disseminated and passed down to future generations, from oral traditions to the written, printed and now digital word. I'm especially interested in moments of major innovation in information distribution and what we can learn from those transition points that can help us better understand our modern moment and how the confluence of digital, social and AI will impact the future of information in society. This means that I often encounter manuscripts and printed works spanning thousands of years and all the world's extant mediums, formats, languages, typescripts and styles: the vast majority of which have little known provenance, little detail and no translations. Can Gemini 2.5 Pro help unlock our ancient past and serve as a digital research assistant: a sort of AI Indiana Jones that can look at any document from history and tell me what it is, where it came from, what it says and why it is important?

Here we explore two sets of printed book pages from 1496 and an illuminated manuscript from the mid-1400s with four illuminated initials. Gemini does a remarkable job of estimating their publication dates, locations and provenance, their composition, materials, pigments and archival storage and display requirements. For the two printed works, it remarkably is able to not only reasonably transcribe and translate their 1496 Schwabacher typeface, but even identify the specific page, column and line in which a given piece of information appears, while for the illuminated manuscript, it offers a detailed assessment of the illuminations and text. Despite using the unmodified public Gemini 2.5 Pro model to examine material that is more than 500 years old in typefaces and language forms rarely represented in the modern world, Gemini performs extremely well on this collection. Given the tremendous promise of these results with the stock Gemini model and the vast digitized holdings of such historical manuscripts held by major museums and archives around the world, it is likely that humanities researchers collaborating with those museums could finetune a model like Gemini on the unique typefaces, inks, materials, languages and layouts of the era to yield near-perfect transcriptions.

Try it for yourself: all of the experiments below were done using AI Studio.

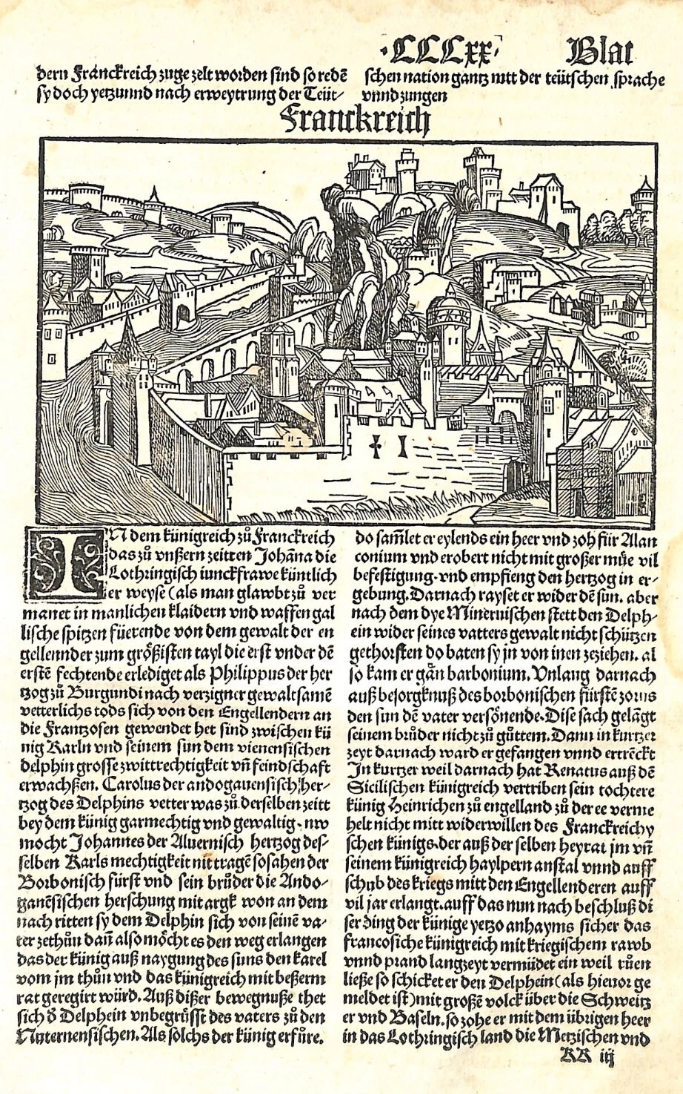

Let's start with this fascinating example. It is a page from a Schonsperger Schedel pirate: an unauthorized German-language edition of the Nuremberg Chronicles from 1496. It initially caught my eye because of the appearance of the word "Johana" in the second line of the first paragraph and given that the page's title is (France), could this be a mention of Joan of Arc from within living memory of her brief life?

Let's ask Gemini 2.5 Pro to transcribe and translate the page:

Transcribe this page in its entirety and then translate into English in its entirety. Do not summarize. Transcribe and translate as-is.

Remarkably, Gemini reveals that this page indeed mentions the historical Joan of Arc:

This is a translation of a page from the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), written in Early New High German. The translation aims to be accurate to the original text while being readable in modern English.

Page 460r

…of the French tongue have been counted, so the [German] nation speaks entirely with the German language; yet now, after the expansion of the people and tongues, [it is called]

France

[Left Column]

Since the kingdom of France was for the greatest part freed from the power of the English—which in our time Joan, the maiden of Lorraine, first accomplished in battle, leading the Gallic forces in men's clothing and armor (having been, as is believed, artfully admonished to do so)—and since Philip, the Duke of Burgundy, turned from the English to the French after the violent death of his kinsman [his father, John the Fearless], great discord and enmity arose between King Charles and his son, the Dauphin of Viennois.

Charles of Anjou, the Dauphin's kinsman, was at that time very mighty and powerful with the king. Now, John of Auvergne, the duke, could not bear the mightiness of this same Charles, so the Bourbon prince and his brother looked upon the Angevin rule with malice. Afterwards, they advised the Dauphin to separate from his father, for in this way it might be achieved that the king, out of inclination for his son, would dismiss Charles from his side, and the kingdom would be ruled with better counsel.

From this agitation, the Dauphin departed to the Lintermensischen [likely a region under his control] without his father's leave. When the king learned of this,

[Right Column]

he then gathered an army and marched to Alençon and conquered many fortifications without great difficulty. And the duke [of Alençon] received him in submission.

Afterward, he traveled against his son. But after the cities of the Minervois did not dare to protect the Dauphin against his father's power, they asked him to depart from them. So he came towards the Bourbonnais. Not long after, the son was reconciled with the father through the mediation of the Bourbon prince. This matter did not please his brother. For a short time thereafter, he was captured and drowned.

A short while after, Renatus [René of Anjou], having been driven out of the Sicilian kingdom, gave his daughter in marriage to King Henry of England, not against the will of the French king. Through this marriage, he obtained a truce in the war with the English for many years.

So that now, after the conclusion of these matters, the king, being now secure at home, let the French kingdom—long tired from the robbery and burning of war—rest for a while. So he sent the Dauphin (as mentioned before) with a large force over Switzerland and Basel. Then he marched with the remaining army into the land of Lorraine against the people of Metz and…

[text continues on the next page]

KK iij

[Printer's signature]

Where exactly is the reference to Joan of Arc on the page?

Where on the page is Joan of Arc mentioned? Tell me the precise column and line number and give me the snippet of text in its original language and translated into English.

Yielding exactly the correct answer:

Of course. Joan of Arc is mentioned near the beginning of the main text block.

Location: Left column, lines 2-3

Original German Snippet

The direct phrase identifying her is:

Johana die Lothringisch iunckfraw

This is the beginning of a longer sentence that describes her actions. Here is the full contextual sentence from the page:

…das zů vnsern zeitten Johana die Lothringisch iunckfraw künſtlich er weyse (als man glawbet) zů vermanet in manlichen klaidenn vnd waffen gallische spitzen füerende von dem gewalt der engellender zum grössisten tayl… erlediget…

English Translation

The translation of the direct phrase is:

Joan, the maiden of Lorraine

And here is the translation of the full contextual sentence:

…which in our time Joan, the maiden of Lorraine… leading the Gallic forces in men's clothing and armor (having been, as is believed, artfully admonished to do so) for the greatest part freed [the kingdom] from the power of the English…

Can Gemini assess the provenance of the page and correctly identify it?

Estimate the typeface, publication date and location and source document that this page came from.

Unfortunately, Gemini is unable to recognize that this is a pirate, despite correctly recognizing it as a Germanic text, though it does perfectly capture its Schedel origins:

Of course. Based on the visual evidence from the page, here is an estimation of its origins:

Summary of Findings

-

- Source Document: The Nuremberg Chronicle (German edition: Das Buch der Chroniken)

- Publication Date: 1493

- Location: Nuremberg, Germany

- Typeface: Schwabacher (a German Gothic / Blackletter script)

Detailed Analysis

1. Source Document and Content

The page is from the Nuremberg Chronicle, one of the most famous and extensively illustrated books of the early printing era (an incunabulum).

-

- Author: The text was compiled by Hartmann Schedel.

- Printer: It was printed and published by Anton Koberger, who was Albrecht Dürer's godfather and one of the most successful publishers of the 15th century.

- Illustrators: The nearly 2,000 woodcut illustrations were created in the workshop of Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff. The famous artist Albrecht Dürer was an apprentice in this workshop at the time and is believed to have contributed to some of the illustrations.

- Content: The book is a world history, chronicling events from the biblical creation to the 1490s. The text on this page discusses the history of France ("Franckreich"), specifically events following the Hundred Years' War involving Joan of Arc (Johana die Lothringisch iunckfraw), King Charles VII, and the Dauphin. This historical content is a perfect match for the Chronicle's scope.

2. Publication Date and Location

The Chronicle was published in 1493 in Nuremberg. Two editions were printed that year: a Latin version (Liber Chronicarum) released in July, and this German version (Das Buch der Chroniken) released in December. The combination of the specific woodcut style, typeface, and layout is uniquely characteristic of Koberger's 1493 publication.

3. Typeface

The typeface is a German Gothic script known as Schwabacher. This blackletter style is less rigid and more rounded than the earlier Textura used by Gutenberg. It was very popular for German-language works printed in Southern Germany, especially Nuremberg, in the late 15th century. Its features are clearly visible in the distinctive shapes of letters like 'g', 'o', and the capital 'S'.

4. Corroborating Evidence on the Page

-

- Page Number: The top right corner shows ".LLLXr Blat". This is Roman numeral formatting for Folio 460, recto (the front side of the leaf). The Chronicle is a massive book, and this page number fits within its structure.

- Woodcut Style: The woodcut is a generic cityscape. A key feature of the Nuremberg Chronicle is that its 1,809 woodcuts were made from only 645 unique blocks. This means the same image of a city, pope, or king was often reused to represent different people and places. This illustration represents "France" as a whole, rather than a specific, identifiable city.

- Printer's Signature: The mark "KK iij" at the bottom right is a quire signature. This mark helped the bookbinder correctly order the folded sheets (gatherings) before sewing them together. This was a standard practice for large, professionally produced books of the period.

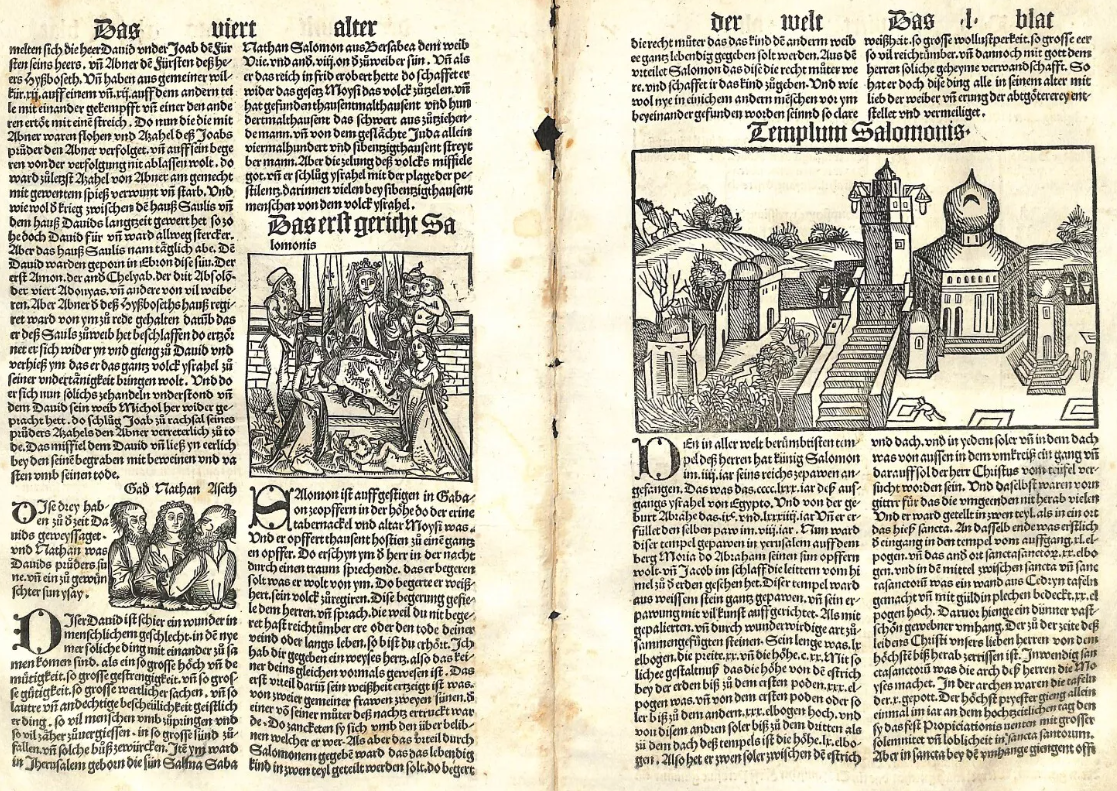

Here's another page that caught my eye, from the same pirate, describing the Temple of Solomon. A previous scholar had cited precise measurements of the Temple in cubits to this book, but neglected to include the page number from which they came. Could this be the page?

Let's ask Gemini:

Does this page contain the precise measurements of the Temple of Solomon? If so, tell me the exact page, column and line numbers and provide the snippet(s) of text in the original language and English that contain those measurements.

Incredibly, Gemini spots them and tells us precisely where to look on the page, though it is unclear whether it correctly translates them:

Yes, the right-hand page of this book spread contains several specific, though perhaps not entirely biblically accurate, measurements for the Temple of Solomon.

The book is a page from the Nuremberg Chronicle (Schedelsche Weltchronik), a famous illustrated world history book first published in 1493. The text is in Early New High German.

The measurements are located on the right-hand page, which is labeled "Das l. blat" (The 50th leaf/page). The relevant text is in the two columns directly beneath the large woodcut titled "Templum Salomonis".

Given the dense paragraph format of this early printed book, precise line numbers are not practical. Instead, the measurements are identified below by the column they appear in and the specific text snippet. The numbers are given in Roman numerals (e.g., cr. for xx, c.rr. for cxx, lr. for lx). The unit of measurement is elñ or elpogen/elbogen, which translates to "ells" or "cubits".

Location 1: Right Page, First Column

This section gives the overall dimensions and the heights of the different floors.

Snippet 1 (Overall Width and Height):

-

- Original German: "…die breite. cr. [xx] vñ die höhe. c.rr. [cxx] elñ…"

- English Translation: "…the width, 20 and the height, 120 cubits/ells…"

Snippet 2 (Height of the Floors):

-

- Original German: "…die höhe von der estrich bey der erden biß zu dem ersten poden. ccc. [ccc] elpogen was. vñ von dem ersten poden oder soller biß zu dem andern. crr. [cxx] elbogen hoch. vñ von disem andern soler biß zu dem dritten als zu dem dach deß tempels ist die höhe. lr. [lx] elbogen."

- English Translation: "…the height from the pavement by the earth up to the first floor was 300 cubits. And from the first floor or gallery up to the second, 120 cubits high. And from this second gallery up to the third, which is the roof of the temple, the height is 60 cubits."

Location 2: Right Page, Second Column

This section describes the interior divisions of the Temple.

Snippet 3 (Entrance and Holy of Holies):

-

- Original German: "…In dasselb was ein vsserlich heügang in den tempel vom auffgang. cl. [cl] elpogen… vñ das sancta sanctorum. rr. [xx] elbogen."

- English Translation: "…In that place was an outer entrance to the temple from the east, 150 cubits… and the Holy of Holies, 20 cubits."

Snippet 4 (Height of the Inner Wall):

-

- Original German: "…was ein wand aus Cedryn roßels gemacht vit mit guldin blechen bedeckt. cr. [xx] elpogen hoch."

- English Translation: "…was a wall made of Cedar wood, covered with golden plates, 20 cubits high."

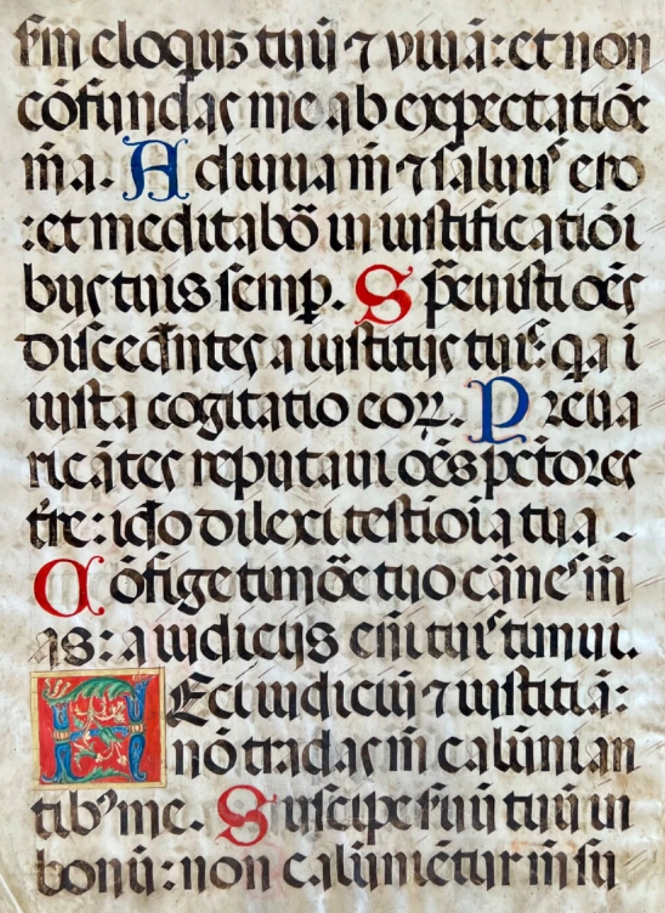

Now let's try a far more complex example – an illuminated manuscript. Let's assess these four illuminated initials that appeared on a mid to late 15th century manuscript and see what Gemini is able to make of them:

Let's start with a freeform query and ask Gemini to "assess their quality":

Assess the quality of these illuminations.

This yields:

Based on the four images provided, here is an assessment of the quality of these illuminations, breaking it down by artistic skill, materials, style, and overall level of production.

These appear to be illuminated initials from a late medieval manuscript, likely from the 15th century, written in a Gothic Textura script. Overall, they represent a good, solid level of provincial or monastic craftsmanship, but they do not reach the level of the highest-end, courtly manuscript production of the same period (e.g., from top Parisian, Burgundian, or Flemish workshops).

Here's a detailed breakdown:

1. The Initial with Two Faces (Possibly a 'C' or 'G')

-

- Artistic Skill: This is arguably the most artistically ambitious of the four. The integration of two bearded male profiles into the foliate form of the letter is a classic medieval "grotesque" or "drolerie" motif. The faces are expressive and have character, but the execution is somewhat rustic. The modeling is basic, using simple brown washes for shading rather than delicate, layered brushstrokes. The linework is confident but a bit thick. The central floral/geometric pattern is well-executed and symmetrical.

- Quality Level: Good. The concept is strong and engaging, but the technical execution of the figures suggests a competent craftsman rather than a master painter. The choice to leave the parchment background unpainted was a common and cost-effective technique.

2. & 3. The Floral/Vase Motifs on Gold Ground

-

- Artistic Skill: These two illuminations are stylistically very similar and represent a higher level of decorative refinement than the first and fourth images. The design, featuring a central vase or candelabrum with scrolling acanthus-like leaves and flowers, shows influence from Italian Renaissance models. The use of fine white pen-work for highlights on the blue and pink elements creates a sense of three-dimensionality and delicacy. The linework is more fluid and elegant here.

- Materials: The use of a gold leaf background (or possibly a high-quality gold paint known as shell gold) immediately elevates the quality and cost of these illuminations. The gold provides a luminous, rich backdrop that was reserved for more valuable commissions.

- Quality Level: Very Good. These demonstrate a higher budget and a more sophisticated decorative sense. The artist was skilled in creating elegant, balanced compositions with a good command of highlighting to create form.

4. The Initial 'H' on Red Ground

-

- Artistic Skill: This initial is more graphic and bold in its design. The letterform is constructed from stylized architectural/plant-like forms. The execution is simpler than in the gold-ground illuminations. The modeling on the blue pillars is less subtle, and the green foliage is somewhat coarse, with thick outlines and simple white dabs for detail.

- Materials: The background is a flat, opaque red paint, a less luxurious and less labor-intensive choice than burnished gold leaf. The color is vibrant and provides a strong contrast, but it lacks the precious quality of gold.

- Quality Level: Good, but more standard. This style is strong and effective but less refined than the previous two. It's a very common type of decoration for a well-made but not extravagantly expensive book.

Overall Assessment:

-

- Consistency: There are stylistic consistencies (the color palette, the type of foliage) that suggest these could be from the same manuscript, possibly decorated by one or two artists in the same workshop. The difference in quality (gold-ground vs. painted-ground) is typical within a single manuscript, where more important sections (like the start of a major chapter) would receive more elaborate decoration.

- Level of Production: These illuminations are far from crude. They are the work of a trained professional illuminator. They likely come from a manuscript made for a well-to-do client like a wealthy merchant, a minor aristocrat, or a prosperous monastery, rather than for a king or duke.

- Condition: The illuminations show signs of age, such as some rubbing, slight flaking of the pigments, and general wear to the parchment. This is typical for a functional manuscript that is over 500 years old.

In summary, you have a collection of high-quality examples of 15th-century provincial book art. They showcase a range of decorative techniques and budgets, from the engaging figurative work and bold graphic initials to the more elegant and expensive floral designs on gold ground. They are excellent artifacts of standard late medieval book production.

Given that these two manuscript leaves were long ago separated from their parent document and context, let's see if Gemini can restore some provenance to them. It is known that the two leaves are from the 15th century. Despite their considerable size (more than one by two feet), they were originally assessed for auction to be part of a Book of Hours, while their size and structure instead suggests an antiphonal or other choral sheet. Let's see what Gemini makes of things:

Can you estimate the year of publication and what publication these were in? also, can you estimate the location they were made?

Indeed, Gemini arrives at the same conclusion – beating the human assessment in this case:

Excellent questions. Based on a close analysis of the script, artistic style, and materials, we can make some well-educated estimates about the manuscript's origin.

Estimated Date: c. 1460 – 1490 (Last Third of the 15th Century)

Reasoning:

-

- Script: The script is a formal Gothic Textura, specifically a Textura Quadrata. This highly formal, angular bookhand was the standard for high-grade liturgical manuscripts (Bibles, Missals, Choir Books) throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. Its use here points to a pre-1500 date, as Humanist scripts began to gain influence after this, although Textura was retained for religious texts well into the 16th century, especially in Germanic regions.

- Illumination Style: The key to the date lies in the stylistic mix.

- The initials on the gold ground (Images 2 & 3) show strong Italian Renaissance influence. The symmetrical arrangement of flowers and leaves growing from a central vase or candelabrum-like form is a classic all'antica ("in the ancient style") motif that became popular in Italy in the mid-15th century.

- This Italian style was adopted by illuminators north of the Alps starting around the 1460s and became widespread by the 1470s and 1480s.

- The manuscript retains a very traditional, heavy Gothic script, indicating that it wasn't produced in Italy (where the script would likely be a rotunda or early Humanist hand).

- This combination of a Northern Gothic script with newly imported Italian decorative motifs perfectly situates the manuscript in the last third of the 15th century.

Estimated Location: Southern Germany or Austria

Reasoning:

-

- The "Hybrid" Style: The fusion of traditional Gothic forms with Italian Renaissance decoration was a hallmark of workshops in regions with strong trade and cultural ties to Italy. Southern Germany (especially cities like Augsburg and Nuremberg) and Austria were primary conduits for the diffusion of Italian artistic ideas into Northern Europe.

- Execution: The style of illumination—bold, confident, and highly competent but not reaching the hyper-refined, jewel-like quality of the top-tier Flemish or Parisian workshops—is very characteristic of major German or Austrian monastic or urban commercial workshops of the period. The initial with the two faces, in particular, has a graphic strength often associated with German art.

- Color Palette: The use of strong greens, blues, and reds, often with white pen-work for highlights, is consistent with illumination from this region.

While France (especially the south, like Avignon) is also a possibility, the specific combination of the heavy Textura script and this particular type of robust floral decoration points most strongly to a Germanic origin.

Estimated Publication Type: A Large Liturgical Choir Book (Antiphonal or Gradual)

Reasoning:

-

- Large Format: The size of the letters and the initials indicates this was a very large book. Such books were not for personal study but for communal use, placed on a lectern so that multiple people could read from it at a distance.

- Formal Script and Decoration: The high formality of the script and the expense of the decoration (including gold leaf) were reserved for the most important books used in church services.

- Likely Candidates:

- Antiphonal (or Antiphoner): Contains the sung portions of the Divine Office (the daily cycle of prayers sung by a choir of monks or canons).

- Gradual: Contains the sung portions of the Mass.

- Missal: Contains the prayers and texts for the priest celebrating the Mass. While often large, the very largest manuscripts were typically for the choir.

Given the scale, an Antiphonal or Gradual is the most probable type of book. These choir books were often massive and needed to be legible to the entire choir. The text fragment in Image 4 showing 18: could be a reference to a psalm or another numbered section within the liturgy, which would be common in such a book.

What kinds of materials were used for the pigments for these illustrations?

Estimate what materials were used for the colors.

Yielding:

Of course. Estimating the materials involves drawing on our knowledge of historical pigment production and the common practices of illuminators in the late 15th century. The palette used here is classic for a high-quality manuscript of this period.

Here is an estimate of the materials used for the colors and other components of these illuminations:

The Pigments (Colors)

The pigments would have been finely ground minerals, earths, or synthetically prepared substances, which were then mixed with a binder to create paint.

-

- Gold: The luminous, shiny background in the second and third images is gold leaf. This was the most expensive and prestigious material after the top-tier blue. The process involved applying thin sheets of beaten gold over a raised base of gesso or bole (a mixture of fine clay, gypsum, and a binder like animal glue). The gold was then burnished with a smooth, hard tool like an agate stone or a wolf's tooth to a brilliant shine.

- Blue: The vibrant blue is one of two high-quality pigments:

- Most Likely: Azurite. A naturally occurring copper carbonate mineral. It was the standard high-quality blue in the 15th century, providing a brilliant, strong color. It was more affordable than its rival, ultramarine.

- Possible (for a very high budget): Ultramarine. Made by grinding the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli, which was imported from Afghanistan. It produced the most brilliant, deep, and stable blue, and was often more expensive than gold. Given the presence of gold leaf, the use of ultramarine is plausible, though high-grade azurite could produce a similar effect.

- Red: The bright, opaque red used for the frames and floral details is almost certainly Vermilion. This was the premier red pigment of the Middle Ages. It's a toxic mercuric sulfide that was either derived from the mineral cinnabar or produced synthetically by alchemists. For a less vibrant or secondary red, Red Lead (minium) could also have been used.

- Green: The strong, leafy green is most likely Verdigris. This is a copper acetate pigment, made by exposing copper plates to acidic vapors like vinegar or wine. It produces a brilliant green but can be unstable over time and sometimes corrodes the parchment. Another possibility is Malachite, a ground mineral related to azurite, which provides a stable and beautiful green.

- Pink/Mauve: This color was typically created by mixing a red lake pigment with Lead White.

- A lake pigment is made from an organic dye (from plants or insects) that is precipitated onto an inert white powder (like chalk or alum). The most likely dye sources would be Kermes (from an insect, creating a crimson color) or Brazilwood (a plant dye).

- Lead White was the standard opaque white pigment, used here to lighten the red lake into a pink and to provide opacity.

- White: The fine highlights that give the forms a three-dimensional quality, as well as the small white flowers, were painted with Lead White (basic lead carbonate). It was prized for its opacity and brightness.

- Brown: The skin tones and beards of the faces in the first initial were rendered using natural earth pigments like ochres and umbers. These were inexpensive, stable, and widely available, perfect for creating naturalistic tones.

- Black (Ink for Script): The text was written with a very dense, black ink. The two main options are:

- Iron Gall Ink: The most common writing ink of the period, made from oak galls, iron sulfate, and a gum binder. High-quality iron gall ink is a deep, velvety black when fresh.

- Carbon Black (Lampblack): Made from soot collected from burning oils or resins. It produces a very stable, deep black and was often used for the most formal scripts.

The Binder

To turn these dry pigments into paint, they were mixed with a liquid binder. For manuscript illumination, the two most common binders were:

-

- Glair: Made from whipped and settled egg whites. It created a viscous, glossy medium that held the pigment well.

- Gum Arabic: Sap from the acacia tree, which created a more matte or semi-matte finish and was excellent for fine details.

In summary, the illuminator used a rich and expensive palette characteristic of a well-funded workshop. The use of gold leaf and a high-quality blue like azurite or ultramarine, combined with the brilliant vermilion, indicates that this was a significant and costly commission.

Given that the illuminations alone are not enough to fully assess the manuscript, let's give Gemini the full-page scans and ask it again to assess provenance:

Here are the full pages in which the illuminations appear. can you estimate date and location of publication and what publication it was? explain your reasoning.

Here are what the full pages looked like:

Yielding:

Excellent. The full pages provide a wealth of new information that allows for a much more confident and detailed analysis. My initial assessments are strongly confirmed and can now be refined with greater precision.

Here is a detailed breakdown of the manuscript's estimated origin, date, and publication type, with the reasoning behind each point.

Publication: Antiphonal (or Antiphoner)

This was a large-format choir book containing the sung portions of the Divine Office (also known as the Liturgy of the Hours), the daily cycle of prayers recited by monks, nuns, or canons.

Reasoning:

-

- Massive Scale: The tape measure in the images shows the parchment leaves are approximately 22 inches (56 cm) tall. This enormous size is the single most telling feature. A book this large was not for personal reading. It was made to be placed on a lectern in the center of a church choir, so that an entire group of singers could read the music and text from a distance. This immediately identifies it as a choir book.

- The Text is Psalm 119 (Vulgate 118): I was able to identify the Latin text on the pages. All four leaves contain sequential portions of Psalm 119 (numbered 118 in the Vulgate Bible used at the time).

- The page with the "G" initial begins Quomodo dilexi legem tuam… (Psalm 119:97: "Oh, how I love your law!").

- The page with the vase initial begins Iniquos odio habui… (Psalm 119:113: "I have hated the unjust…").

- The page with the "H" initial begins In aeternum Domine… (Psalm 119:89: "For ever, O Lord, thy word standeth firm in heaven.").

Psalm 119 is the longest psalm and is the backbone of the daily prayer cycle in the Divine Office, recited in full every day. Its prominent place in these leaves makes an Antiphonal the most likely type of book. A Gradual (containing music for the Mass) is also a possibility, but the extensive treatment of this specific psalm strongly points to the Divine Office.

- Layout and Decoration: The layout is typical for a high-grade liturgical book: a single column of large, clear script, with important verses marked by large, decorated initials (like the 'H', 'G', and the vases). Smaller verses are marked by simpler red and blue Lombardic capitals. The red letters (rubrics) provided instructions or marked beginnings of sections.

Date of Publication: c. 1470 – 1490

This manuscript was almost certainly produced in the last third of the 15th century.

Reasoning:

-

- Script: The script is a highly formal and conservative Gothic Textura Quadrata. This hand was standard for luxury liturgical manuscripts in the 15th century. It shows no influence from the newer Humanist scripts that would become more common after 1500.

- Illumination Style (The "Smoking Gun"): The decorative style is a fascinating and dateable hybrid.

- Gothic Foundation: The structure of the initials, the use of grotesque faces (in the 'G'), and the bold, graphic quality of the 'H' are rooted in Northern European Gothic traditions.

- Italian Renaissance Influence: The key to the date is the style of the vase/candelabrum initials on the gold ground. This symmetrical, classicizing floral motif, inspired by ancient Roman art, is a hallmark of the Italian Renaissance. This style was adopted by illuminators north of the Alps starting around the 1460s and became very fashionable in the 1470s and 1480s.

The combination of a traditional Gothic script with this trendy Italianate decoration firmly places the manuscript in the period when these new ideas were being absorbed into established workshops.

Location of Publication: Southern Germany or Austria

The manuscript was most likely produced in a major artistic center in Southern Germany (such as Augsburg or Nuremberg) or Austria (such as Salzburg).

Reasoning:

-

- The Center of the Hybrid Style: These regions were the primary conduits through which Italian Renaissance art and ideas flowed into Northern Europe. They had strong trade, religious, and political ties with Northern Italy. Workshops in this area were famous for creating exactly this kind of stylistic fusion: retaining the strong, heavy character of German Gothic art while eagerly incorporating new decorative motifs from the south.

- Artistic Execution: The style is robust, confident, and very high quality, but it lacks the extreme delicacy and atmospheric perspective of top-tier contemporary Flemish illumination (from Bruges or Ghent). It also lacks the pure classicism of a purely Italian manuscript. The bold lines, strong colors, and graphic power are very characteristic of the best Germanic work of the period.

- Foliation Numbers: The numbers "44" and "48" in the bottom right corner are leaf numbers (folios) added in a later, simpler hand. The fact that leaves are missing between 44 and 48 is typical for manuscripts that were later disassembled for sale as individual leaves.

Summary

You have four leaves from a magnificent and very expensive Antiphonal, produced around 1470-1490 in a major workshop in Southern Germany or Austria. It was commissioned for a wealthy cathedral or monastery, where it would have been used daily by the choir for their sung prayers, representing a significant investment in the beauty and solemnity of their worship.

Let's assume our Textura and Latin is a bit rusty. Can Gemini read Gothic Textura typescript from 500 years ago and translate Latin from that era into English?

Arrange the four pages in order and transcribe them in their entirety word-for-word. Then translate them into English in their entirety. Do not summarize, transcribe and translate them exactly as they appear.

This yields the following. Unfortunately, it appears that Gemini struggled with the Textura typescript and heavily hallucinated, though there are some interesting glimmers here and it is clear that with tuning Gemini could likely be made to natively understand it. As a reminder, we used the stock Gemini 2.5 Pro for this work, which is unlikely to have been heavily tuned for older typefaces and languages. It is likely that with dedicated finetuning, these results would be enormously improved:

Of course. Based on the biblical text, I have arranged the four full manuscript pages in their correct liturgical and chronological order.

The text on all four leaves comes from Psalm 119 (numbered as Psalm 118 in the Latin Vulgate Bible, which this manuscript uses). This is the longest psalm and a cornerstone of the Divine Office.

A note on the transcription: I have transcribed the Latin exactly as written but have expanded the scribal abbreviations for readability. For example, a line over a vowel indicates a missing 'm' or 'n' (e.g., dñe becomes domine), and special symbols are used for common endings like -rum and syllables like per- or pro-. The punctuation is transcribed as it appears.

Page 1 (Initial 'H' – Folio 44)

Psalm 119 (118): 89-96

Transcription

In eternum domine verbum tuum permanet in celo.

In generationem et generationem veritas tua: fundasti terram et permanet.

Ordinatione tua perseuerat dies: quoniam omnia serviunt tibi.

Nisi quod lex tua meditatio mea est: tunc forte periissem in humilitate mea.

In eternum non obliviscar iustificationes tuas: quia in ipsis vivificasti me.

Tuus sum ego salvum me fac: quoniam iustificationes tuas exquisiui.

Me expectaverunt peccatores ut perderent me: testimonia tua intellexi.

Omnis consummationis vidi finem: latum mandatum tuum nimis.

Translation (Douay-Rheims Bible)

For ever, O Lord, thy word standeth firm in heaven.

Thy truth endureth unto all generations: thou hast founded the earth, and it continueth.

By thy ordinance the day goeth on: for all things serve thee.

Unless thy law had been my meditation, I had then perhaps perished in my abjection.

Thy justifications I will never forget: for by them thou hast given me life.

I am thine, save thou me: for I have sought thy justifications.

The wicked have waited for me to destroy me: but I have understood thy testimonies.

I have seen an end of all perfection: thy commandment is exceeding broad.

Page 2 (Initial 'G')

Psalm 119 (118): 97-104

Transcription

Quomodo dilexi legem tuam domine: tota die meditatio mea est.

Super inimicos meos prudentem me fecisti mandato tuo: quia in eternum mihi est.

Super omnes docentes me intellexi: quia testimonia tua meditatio mea est.

Super senes intellexi: quia mandata tua quesiui.

Ab omni via mala prohibui pedes meos: ut custodiam verba tua.

A iudiciis tuis non declinavi: quia tu legem posuisti mihi.

Quam dulcia faucibus meis eloquia tua: super mel ori meo.

A mandatis tuis intellexi: propterea odivi omnem viam iniquitatis.

Translation (Douay-Rheims Bible)

O how have I loved thy law, O Lord! it is my meditation all the day.

Through thy commandment, thou hast made me wiser than my enemies: for it is ever with me.

I have understood more than all my teachers: because thy testimonies are my meditation.

I have had understanding above ancients: because I have sought thy commandments.

I have restrained my feet from every evil way: that I may keep thy words.

I have not declined from thy judgments, because thou hast set me a law.

How sweet are thy words to my palate! more than honey to my mouth.

By thy commandments I have had understanding: therefore have I hated every way of iniquity.

Page 3 (Vase Initial – Folio 48)

Psalm 119 (118): 113-120

Transcription

Iniquos odio habui: et legem tuam dilexi.

Adiutor et susceptor meus es tu: et in verbum tuum supersperavi.

Declinate a me maligni: et scrutabor mandata dei mei.

Suscipe me secundum eloquium tuum et vivam: et non confundas me ab expectatione mea.

Adiuva me et salvus ero: et meditabor in iustificationibus tuis semper.

Sprevisti omnes discedentes a iudiciis tuis: quia iniusta cogitatio eorum.

Prevaricantes reputavi omnes peccatores terre: ideo dilexi testimonia tua.

Confige timore tuo carnes meas: a iudiciis enim tuis timui.

Translation (Douay-Rheims Bible)

I have hated the unjust: and have loved thy law.

Thou art my helper and my protector: and in thy word I have greatly hoped.

Depart from me, ye malignant: and I will search the commandments of my God.

Uphold me according to thy word, and I shall live: and let me not be confounded in my expectation.

Help me, and I shall be saved: and I will meditate always on thy justifications.

Thou hast despised all them that fall off from thy judgments; for their thought is unjust.

I have accounted all the sinners of the earth prevaricators: therefore have I loved thy testimonies.

Pierce thou my flesh with thy fear: for I am afraid of thy judgments.

Page 4 (Initial 'F')

Psalm 119 (118): 121-128

Transcription

Feci iudicium et iustitiam: non tradas me calumniantibus me.

Suscipe servum tuum in bonum: non calumnientur mihi superbi.

Oculi mei defecerunt in salutare tuum: et in eloquium iustitie tue.

Fac cum servo tuo secundum misericordiam tuam: et iustificationes tuas doce me.

Servus tuus sum ego: da mihi intellectum ut sciam testimonia tua.

Tempus faciendi domine: dissipaverunt legem tuam.

Ideo dilexi mandata tua super aurum et topazion.

Propterea ad omnia mandata tua dirigebar: omnem viam iniquam odio habui.

Translation (Douay-Rheims Bible)

I have done judgment and justice: give me not up to them that slander me.

Uphold thy servant unto good: let not the proud calumniate me.

My eyes have failed for thy salvation: and for the word of thy justice.

Deal with thy servant according to thy mercy: and teach me thy justifications.

I am thy servant: give me understanding that I may know thy testimonies.

It is time for the Lord to do: they have dissipated thy law.

Therefore have I loved thy commandments above gold and the topaz.

Therefore was I directed to all thy commandments: I have hated all wicked ways.

Now let's say we are a library that deals with modern materials and unexpectedly received this manuscript as a gift and want to know how to properly store and display it:

How would you best store this manuscript in archival boxes to preserve it for the future? What kind of materials (buffered, unbuffered), etc should we use? Can it be stored with other vellum and paper materials? In the future if we want to put on display, what kind of lighting, etc should be used to display it?

Yielding the following. Fascinatingly, despite never telling Gemini it was written on vellum, it either assessed that visually or knew based on its age and document type. Gemini correctly assesses that the vellum base requires an unbuffered acid and lignin free box and helpfully suggests unbuffered tissue as a future protective layer.

Of course. This is a critical question. Proper storage and display are essential to ensure these valuable and fragile manuscript leaves survive for another 500 years. As these are on vellum (animal skin), not paper, the rules are slightly different and more stringent.

Here is a comprehensive guide based on professional conservation standards.

Part 1: Archival Storage

Your primary goal for long-term storage is to create a stable, chemically inert, and physically protective environment.

1. The Ideal Environment (The "Macro" Climate)

Before you even think about boxes, control the room where they are stored.

-

- Temperature: Keep it cool and stable. The ideal range is 60-68°F (15-20°C). Avoid attics, basements, and areas near radiators or vents. Stability is more important than the exact number; rapid fluctuations cause the vellum to expand and contract.

- Relative Humidity (RH): This is the single most important factor for vellum. It is hygroscopic, meaning it readily absorbs and releases moisture from the air.

- Ideal Range: 40-50% RH.

- Too high (>60%): Risk of mold growth and the vellum becoming limp and "cockling" (waving).

- Too low (<30%): Vellum becomes brittle, inks can crack, and pigments can flake off.

- Light: Store them in total darkness. Light damage is cumulative and irreversible.

2. The Storage Enclosure (The "Micro" Climate)

You will create a multi-layered enclosure for each leaf. Store them flat. Never roll or fold them.

Step-by-Step Guide:

-

- Individual Folders: Place each manuscript leaf inside its own individual folder.

- The folder should be made of unbuffered, acid-free, lignin-free material.

- You can buy pre-made folders or make them from archival-grade board.

- Optional but Recommended: Place a sheet of unbuffered, acid-free tissue paper on top of the illuminated side of the leaf inside the folder. This provides a soft, non-abrasive protective layer.

- Archival Box: Place the individual folders flat inside a high-quality archival storage box.

- A clamshell box is the professional standard. It's rigid and provides excellent physical protection.

- The box itself should also be made of acid-free, lignin-free board. Whether the box is buffered or unbuffered is less critical than the folder the leaf is in direct contact with, but an unbuffered box is the safest choice.

- Individual Folders: Place each manuscript leaf inside its own individual folder.

3. Key Material Choice: Buffered vs. Unbuffered

This is a crucial distinction for your manuscript.

-

- Buffered Material: Contains an alkaline reserve (usually calcium carbonate) to neutralize acids. This is excellent for most paper, which is often acidic from its manufacturing process.

- Unbuffered Material: This is pH-neutral but has no alkaline reserve. This is the correct and safe choice for your vellum leaves.

Why Unbuffered for Vellum?

Vellum is a protein (collagen). Proteins are stable in a neutral environment. Storing them in a highly alkaline (buffered) environment can, over very long periods, cause a chemical reaction that accelerates the degradation of the protein structure. Furthermore, some historical pigments (especially certain blues and greens) can change color when in direct contact with an alkaline substance.

Conclusion: Always use UNBUFFERED materials (folders, tissue) for anything that will touch your manuscript leaves.

4. Storing with Other Materials

Can it be stored with other vellum?

Yes, as long as each leaf has its own protective folder. Do not stack them directly on top of each other without interleaving.

Can it be stored with paper materials?

It is best to store them separately. If you must store them in the same box, ensure the vellum leaves are in their own unbuffered folders and the paper items are in their own (preferably buffered) folders. This prevents any potential acid migration from the paper to the vellum. Never let them touch directly.

Part 2: Future Display

Displaying an artifact always carries a risk, as it exposes it to light and environmental fluctuations. The goal is to minimize this risk as much as possible.

1. Lighting: The Biggest Threat

Light damage is caused by both the intensity of the light and its UV content.

-

- No Sunlight: Absolutely never display these in direct sunlight. Even indirect sunlight from a window is extremely damaging.

- Light Source: Use LED lights with a high Color Rendering Index (CRI). They emit almost no UV radiation and very little heat. Avoid older fluorescent tubes (high UV output) and incandescent/halogen bulbs (high heat output).

- Light Intensity (Lux Level): For highly sensitive materials like manuscripts with pigments, the conservation standard is a maximum of 50 lux. This is quite dim, similar to the lighting in a top-tier museum's manuscript gallery. Use a light meter app on your phone for a rough estimate, but a real light meter is better.

- Duration: Light damage is cumulative. The shorter the display time, the better. Professional institutions rotate items on display, showing them for only 3-6 months every few years.

2. Framing and Mounting

If you choose to frame them for display, it must be done to full conservation standards.

-

- All materials must be archival: Use 100% cotton rag museum board for the matting. Again, the mat board touching the vellum should be unbuffered.

- No Direct Contact with Glazing: The vellum must never touch the glass or acrylic. Use deep mats or spacers to create an air gap. This is vital because vellum can cockle with humidity changes, and if it touches the glazing, moisture can be trapped, causing mold, and the pigments can stick to the surface.

- UV-Filtering Glazing: This is non-negotiable. Use museum-grade glazing that filters out 99% of UV radiation.

- Museum-grade acrylic (Plexiglas) is often preferred over glass because it's lighter, shatter-resistant, and can offer better static protection.

- Museum Glass is also an excellent option.

3. Environment

The stable temperature and humidity requirements (60-68°F, 40-50% RH) still apply during display. Do not hang it on an outside wall, which can be colder and damper, or above a fireplace or heat source.

Summary & Final Recommendation

| Feature | Storage (Best Practice) | Display (Best Practice) |

| Enclosure | Unbuffered folder in a clamshell box | Conservation frame with unbuffered mat |

| Placement | Stored flat, in the dark | Hung vertically, away from traffic |

| Light | Total darkness | Max 50 lux, no UV, LED lights only |

| Temperature | Stable 60-68°F (15-20°C) | Stable 60-68°F (15-20°C) |

| Humidity (RH) | Stable 40-50% | Stable 40-50% |

| Materials | UNBUFFERED, acid-free, lignin-free | UNBUFFERED mat, UV-filtering acrylic/glass |

| Duration | Indefinite | Short-term only (e.g., 3 months every 5 years) |

Recommendation: Before you purchase materials or attempt to frame these, I strongly advise you to consult a professional paper or book conservator. They can assess the condition of the leaves (e.g., check for pigment flaking), recommend specific archival suppliers, and can create custom enclosures or frames that are perfectly suited to the artifacts. Given their age and quality, a small investment in professional advice will ensure their preservation for generations to come.