Last month Harvard’s HealthMap initiative garnered quite a bit of press for detecting early mentions of the current Ebola outbreak in March 2014, "nine days before the World Health Organization formally announced the epidemic.” HealthMap monitored its first mentions of the outbreak on March 14, 2014 and issued its first alert on March 19, 2014. Coverage of this feat focused on how the site “scour[s] tens of thousands of social media sites … infectious-disease physicians’ social networks and other sources,” emphasizing in particular that “informal sources are helping paint a picture of what’s happening.”

Much of the coverage of HealthMap’s success has emphasized that its early warning was due to its monitoring of these informal and social media channels. For example one blog stated “So how did a computer algorithm pick up on the start of the outbreak before the WHO? As it turns out, some of the first health care workers to see Ebola in Guinea regularly blog about their work. As they began to write about treating patients with Ebola-like symptoms, a few people on social media mentioned the blog posts. And it didn't take long for HealthMap to detect these mentions.”

This got us wondering how GDELT faired at detecting the earliest glimmers of the outbreak given that it currently only monitors global news media and does not penetrate the same kinds of social media and specialized medical alert networks that HealthMap monitors. Would just monitoring news media have offered any kind of advanced warning? The answer, it turns out, is that GDELT actually beat HealthMap by a day.

The first formal public international warning of the impending epidemic actually came not from social media, but from traditional news media: an article in Xinhua’s French-language newswire titled “Guinée: une étrange fièvre fait 8 morts à Macenta” published late in the day EST on March 13, 2014. The article reports that “a disease whose nature has not yet been identified has killed 8 people in the prefecture of Macenta in south-eastern Guinea … it manifests itself as a hemorrhagic fever…” In turn, this newswire article was actually simply reporting on a formal announcement made earlier in the day by Dr. Sakoba Keita, director of the Division of Disease Prevention in the Guinea Department of Health, broadcast nationally on state television, that announced both the outbreak of the unknown hemorrhagic fever and the departure of a team of government medical personnel to the area to investigate it in more detail. The Government of Guinea also formally notified the WHO of the outbreak, meaning the WHO was aware of the outbreak from an early stage.

GDELT monitored this earliest mention of the outbreak as it was published, as well as the considerable surge of domestic coverage of the unknown outbreak the following day, on March 14th. Unfortunately, GDELT is currently only able to translate a portion of global news media each day – it does not yet have the resources to translate 100% of all daily global news media, and thus this material was monitored and flagged, but GDELT was unable to fully process the material with its Event and Global Knowledge Graph algorithms to identify the hemorrhagic references and send a formal alert to the public interface. The formal alert indicating both hemorrhagic fever and the possible diagnosis of Ebola was finally issued on March 20th, one day after HealthMap issued its formal alert, and still three days before the WHO issued its formal alert on the outbreak.

There are several key findings here deserving of further exploration:

- GDELT actually picked up the earliest mentions of the outbreak, beating HealthMap by a day, and those mentions were sufficiently grave at the time to indicate significant potential for critical impact. By the time HealthMap monitored its first isolated mention of the outbreak, GDELT was already monitoring a considerable surge in domestic coverage of the outbreak. By the time HealthMap actually issued its first formal alert on March 19th, GDELT had already been observing a critical surge for more than a week.

- The ability to codify languages other than English is absolutely critical to monitor domestic information streams of greatest relevance to early warning tasks. In this case, GDELT successfully monitored and flagged the earliest indicators of this outbreak in the French-language press, but its current inability to fully translate 100% of global media each day meant its public-facing algorithms were not able to codify these articles and thus did not send out an alert on March 13th or 14th as more information became known. However, as GDELT continues to rapidly expand its translation capabilities to translate an ever-increasing percentage of the world’s news media, it will be able to codify more and more of these earliest indicators.

- Local media is absolutely imperative to access the earliest warning signals of impending situations. Monitoring systems which make use only of international or Western press will find themselves unable to capture many early warning indicators.

- Despite all of the discussion of social media surpassing the mainstream media as an information source, mainstream media actually offered the earliest actionable indicators in this case, beating the social signals monitored by HealthMap. This is a key finding in that despite all of the attention and hype paid to social media as a sensor network over human society, mainstream media still plays a critical role as an information stream in many areas of the world. This is not to say that there were not far earlier signals manifested in the myriad social conversations among medical workers and citizens in the region, only that it was not these indicators that HealthMap detected and alerted on – it was the discussion of the formal government announcement of the outbreak on national television. There is enormous potential for social media as an early warning indicator, but we must move beyond the hype towards work that truly understands how it is used and how information transfers between modalities and across social channels.

- Not a single major media outlet covering the HealthMap alert has mentioned that in fact the earliest warning signals on March 13th and March 14th were actually the outcome of formal announcements made on state television by the Government of Guinea that it had identified and was investigating a hemorrhagic fever outbreak, rather than a computer sifting through millions of social media posts and divining hidden patterns indicating a previously unrecognized pattern of disease that was then used to alert the Government of Guinea. Instead, media coverage of the alert focused on how many days it took for the WHO to issue its formal alert on the outbreak. While both GDELT and HealthMap flagged the earliest warning signals of the outbreak 10 days and 9 days, respectively, before the WHO’s formal pronouncement, thus “beating” the WHO, in reality, NEITHER of the two projects “beat” the Government of Guinea: they were merely picking up the discussion and coverage resulting from the formal state television announcement of the outbreak. This is perhaps the most important takeaway here – who is an early warning alert being issued to? The Government of Guinea obviously did not need to rely on an alert service in the United States to notify it that it had an outbreak that it should look into – it was the source of the information leading to that alert. Instead, the utility of projects like GDELT and HealthMap in monitoring the world for disease outbreaks lies in their ability to offer a globally-scoped view that transcends national boundaries. In this way, health organizations and governments are able to see emerging regional trends that cross borders, while domestic health professionals are able to gain a 30,000-foot view of how the disease is spreading both in and near their communities in order to better prepare their constituents, translating thousands of textual reports and medical summaries into alerts and visuals that allow trends to be more readily understood and acted upon.

The fact that GDELT caught the earliest glimmers of the Ebola outbreak a day before other services, and, a day after that, monitored a massive surge in coverage indicative of rapidly spreading concern of the outbreak and suggestive of its growing significance a week before other services issued their first alerts, suggests that GDELT has enormous potential for early warning of emerging outbreaks and pandemics. Further, as GDELT’s translation infrastructure continues to rapidly expand to translate all foreign language material it monitors throughout the globe in realtime, GDELT’s ability to flag the earliest indicators of emerging situations throughout the world will only continue to grow.

When we talk about “beating the news” or “beating the WHO” and alerting or forecasting future outbreaks or political instability, we have to be careful to think more about whose news we’re “beating.” In the case of Ebola, contrary to much of the news coverage of HealthMap’s alerts, the project did not sift through millions of informal media posts and find a hidden pattern that it used to alert an unsuspecting Guinean Government who then took action to investigate the situation. The Guinean Government was all too aware of the emerging outbreak and had in fact already formally alerted the WHO. Thus, “beating” the WHO’s pronouncement that there was an emerging outbreak by 10 or 9 days did indeed “beat” the WHO to its official announcement to the general public, but certainly did not “beat” the Guinean Government. Similarly, when we talk about “beating the news” the metrics cited are traditionally beating the headlines of large national or international newspapers, while more often than not small local news sources in the affected region have been intensely covering the situation for days. In some regions of the world it is common practice to formally announce events like protests well in advance, advertising them on social media with the precise date, time, and street corner to meet up. Compiling these announcements into a spreadsheet each day is not “forecasting future protests” nor is it even “beating the news” – it is merely filtering. That’s not to say that it is not extremely useful and could offer a transformational shift in American policymakers’ access to that information, but it is simply the equivalent to syndicating a press release, not divining deeply hidden patterns across millions of data points and issuing a forecast. To put it in simpler terms, it represents the difference between republishing Apple's press release from last week announcing the details of its new Apple Watch which it has formally released to the public, versus producing a forecast today of what Apple will be releasing as its next big new product next fall. The problem is that a formal national broadcast by the health ministry of a small African country of a disease outbreak will likely receive far less global attention than the latest Apple product. While that Apple product will appear in headlines in papers across the world, that health announcement from an African country likely won’t reach far beyond its own borders, meaning that we must increasingly reach further and further local to access those kinds of alerts and synthesize them within the context of the evolving local, regional, and global information environments. Instead of trying to “beat” the international news, we should instead be focusing on first doing better at simply paying attention to the local news in the areas we’re interested in – that will get us far closer to our goals at far lower costs and, most critically, offers the great opportunities to collaborate with the local communities that are the best information sources on local events. The goal of GDELT is to do precisely this, to offer a global informational base to support increasingly local monitoring and feedback and increasingly high-resolution alerts and forecasts by providing a computational platform for monitoring the world that goes to great lengths to access local sources throughout the globe.

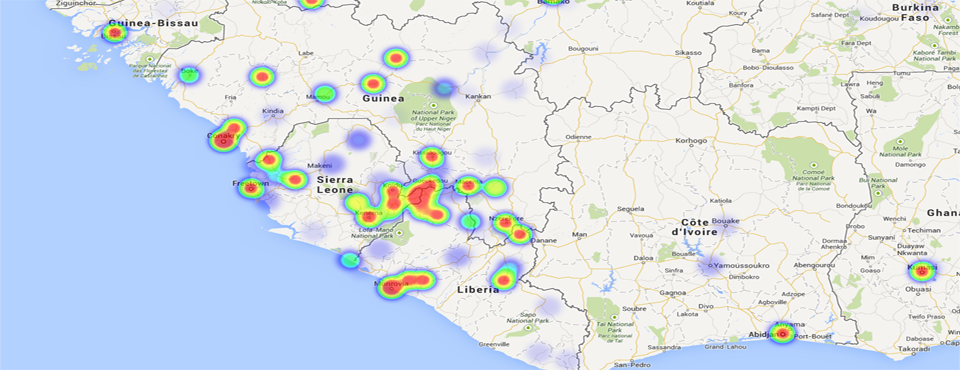

We are incredibly excited to see how remarkably well GDELT faired in monitoring the earliest indicators of the current Ebola outbreak, as well as its ability to map the surrounding stability context of the outbreak as it continues to evolve. We are already beginning to further explore how GDELT can be used as an early warning indicator for disease outbreak and especially how its unique ability to combine that with socio-cultural indicators and realtime social instability can be used to more accurately monitor, assess, visualize, and forecast both the spread of disease and its impact on the stability of nations.